When the River Won’t Sit Still: Flood Monitoring in the Age of Atmospheric Rivers

Headlines tend to focus on flooded streets and closed highways. But for engineers and emergency response teams, the harder problem sits one layer deeper: understanding how fast conditions are changing and where impacts are likely to emerge next.

Because flooding is rarely just flooding.

Flooding is Rarely the Only Hazard

When intense rainfall falls on saturated ground, melting snow, or fire-scarred slopes, a single storm system can activate multiple geohazards at the same time:

· Rivers rise and spill beyond their banks

· Banks erode and scour deepens

· Channels migrate laterally, sometimes aggressively

· Slopes fail, reactivating old landslides or creating new ones

· Infrastructure — pipelines, utilities, culverts, roads, bridges — quietly loses the ground it was relying on

Recent events across the West Coast made this coupling hard to ignore. In Washington, flooding coincided with slope failures that closed major transportation corridors. In British Columbia, road closures and evacuation alerts highlighted how quickly access can disappear when rivers and hillsides respond together. And in California, a landslide-linked natural gas pipeline rupture near the I-5 forced evacuations and shut down a major interstate.

The Hard Part Isn’t the Alert — It’s the Interpretation

Flood response is often treated as a simple threshold problem: water goes up, an alert triggers, action follows.

Most flood monitoring programs rely on real-time hydrometric gauges, converting water level into discharge using rating curves and comparing those flows against predefined thresholds — 20- or 100-year return periods, site-specific concerns, or both.

When an alert arrives, the first question isn’t “Is this bad?” It’s “Is this real?”

Engineers immediately start asking:

· Does the hydrograph make sense, or is this a false peak?

· Is the gauge actually representative of the site, or just nearby on a map?

· Are neighboring watersheds responding the same way?

· Is there a plausible trigger — rainfall, rain-on-snow, dam operations — that explains the magnitude and timing?

False peaks happen. Ice jams happen. Data glitches happen. And dismissing a real signal — or overreacting to a bad one — both carry consequences.

Flood monitoring, done properly, isn’t about eliminating uncertainty. It’s about building confidence in decisions despite it.

Time Is the Real Constraint

One of the less visible challenges during atmospheric river events is that hazards don’t activate all at once.

Rain may stop, but rivers continue to rise. Peak flows pass, but bank failures lag behind. Slopes that held during the storm may fail days later, once pore pressures catch up.

This is where situational awareness matters more than any single dataset.

During the recent atmospheric river impacts in BC and Washington, response teams were juggling real-time flow data, precipitation forecasts, satellite imagery, field observations, and public advisories — often across jurisdictions and organizations. The risk wasn’t a lack of information. It was fragmentation.

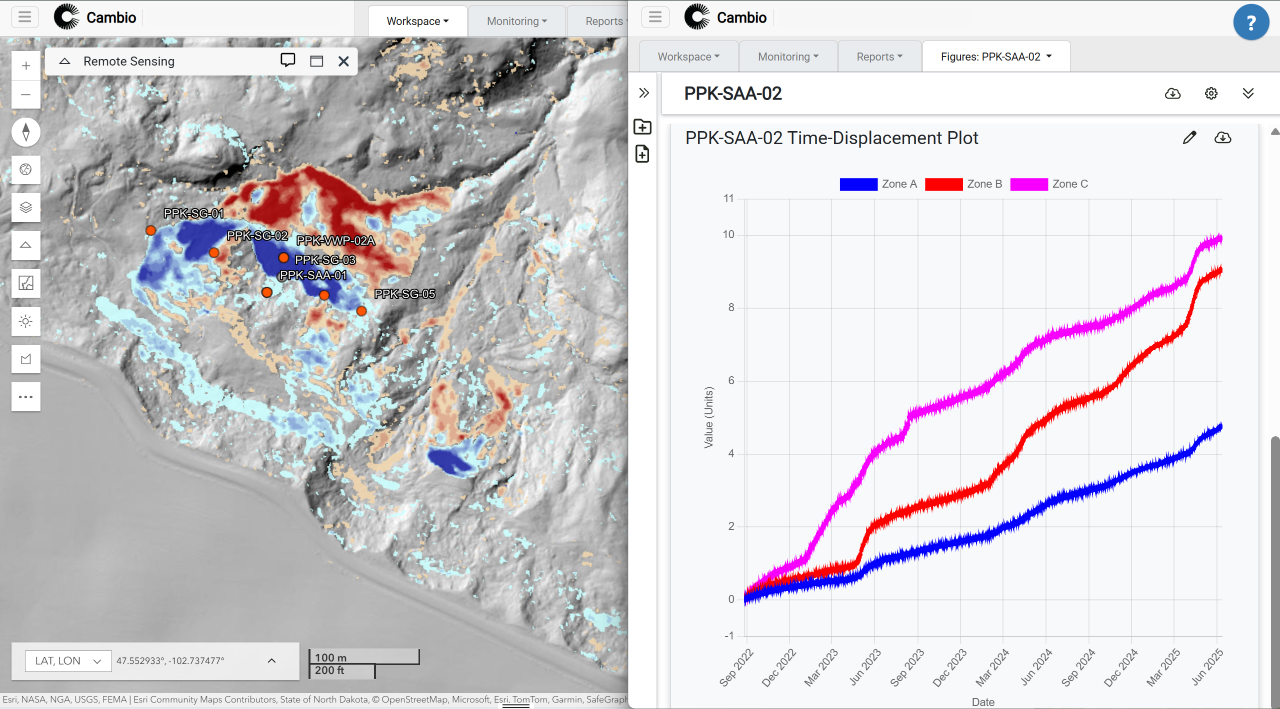

Within about an hour of learning that Canada Task Force One was being mobilized, we stood up a dedicated “2025 Atmospheric River Response” Cambio™ workspace to centralize flood-related data, imagery, inundation extents, and landslide observations. That shared environment has since supported teams from BGC Engineering, local municipalities, park services, and government agencies on both sides of the border.

Not to replace decision-makers — but to give them a clearer, shared picture of what was unfolding.

Because when conditions are evolving by the hour, the ability to answer “what’s changed since the last briefing?” can be just as important as knowing the peak flow.

Flood Monitoring as Risk Management, Not Prediction

There’s a persistent myth in geoscience that good monitoring should make hazards predictable. In reality, the goal is more modest — and more useful.

Flood monitoring exists to:

· Reduce surprise

· Shorten response times

· Support defensible, transparent decisions

· Help teams distinguish between noise and meaningful change

Sometimes that means escalating quickly: recommending inspections, aerial patrols, or operational adjustments. Other times it means not escalating — documenting why an alert doesn’t represent site conditions, and sparing teams unnecessary disruption.

Both outcomes matter. And as climate-driven extremes continue to push systems outside historical norms, the value of disciplined, science-first monitoring only increases.

Showing Up When It’s Messy

Atmospheric rivers don’t respect administrative boundaries, asset classes, or project scopes. They test the seams between disciplines: hydrotechnical, geotechnical, environmental, and operational.

In those moments, the challenge isn’t a lack of data — it’s the opposite. River levels, rainfall grids, satellite imagery, field photos, advisories, emails, spreadsheets, and text messages all start arriving at once. Under pressure, critical context can get lost, duplicated, or siloed just when clarity matters most.

This is where tools need to work the way engineers do.

During the recent atmospheric river impacts in British Columbia and Washington, Cambio helped teams bring flood-related information into a shared, real-time workspace: streamflow alerts, precipitation, imagery, inundation extents, and landslide observations — all tied back to specific sites and assets.

By centralizing information and preserving context — what was reviewed, what was dismissed, and why — teams were able to coordinate across organizations and jurisdictions without losing the thread of the story as conditions evolved hour by hour.

That ability to move quickly isn’t about speed for its own sake. It’s about reducing friction at exactly the moment when uncertainty is highest and decisions still need to be defensible.

Because in the middle of an event, engineers don’t need more alerts. They need a clearer way to understand which ones matter — and how today’s signals connect to yesterday’s assumptions.

When the Water Recedes, the Work Isn’t Over

Flood monitoring helps teams understand what’s happening in near real time. But once the water recedes, a different question emerges:

What changed?

In several disaster response efforts — including post-hurricane deployments — lidar helped engineers re-establish a reliable baseline before inspections, repairs, or reactivation decisions are made. That context matters. Designing or reopening infrastructure using pre-event assumptions can quietly carry risk forward.

After major storm events, rapid lidar acquisition can play a critical role in recovery and reassessment. High-resolution elevation data makes it possible to detect channel migration, quantify scour and deposition, and identify subtle ground deformations that may not be visible from the road or captured in post-event photos.

When paired with flood monitoring data, post-event lidar helps close the loop: connecting what was observed during the event with how the landscape actually responded.

Because resilience isn’t just about getting through the storm. It’s about understanding what the storm left behind.

From Theory to Practice

If this resonates, join us on February 26 at 1 PM PST for an educational webinar on how to set up a flood monitoring program, with practical guidance on thresholds, alerting, and decision-making — plus a panel discussion with BGC engineers who’ve been in the field during recent atmospheric river events.

.svg)

%20Large.jpeg)

.png)